The Yak Online Governance Primer

How do you do online governance? This primer is intended as a guided tour through a curated set of readings—based on a year of study by the Yak Collective*—that can help groups and organizations navigate this question. In selecting the readings we cast a wide net, but in our discussions we made an effort to consider them from the specific perspective of online governance challenges. We believe the ideas surveyed here are applicable to groups and organizations with widely varied purposes, levels of autonomy, degrees of decentralization, and technological sophistication.

How should online communities and virtual organizations be governed? Every organization that has gone virtual to even a small degree should be interested in this question. The range of possible answers spans the gamut from conservative to radical. Online digital technologies allow you to either make incremental tweaks to selected bits and pieces of an organization, or radically rethink every part of it. The fate of your organization depends on making the right choices for the specific challenges it faces.

Starting in mid-2020, a Yak Collective study group has been meeting weekly to explore the question of online governance, one reading at a time. This paper is based on 49 readings we studied in our first year. The full list is included in the Annotated Bibliography section at the end of this paper.

At one extreme of the range of answers we find organizations that seek to evolve their traditions in minor, cosmetic ways; they run the risk of digital transformation being pure theater.

At the other extreme, the adoption of genuinely radical organizational forms such as DAOs (decentralized autonomous organizations) forces the deep redesign of traditional governance mechanisms. Such innovation leads to the risk of failure of initiatives that might have succeeded had they been organized along more conventional lines.

We believe this primer will be of value whether you’re part of a mature traditional organization just beginning to develop significant online operations, perhaps due to the impetus of the Covid pandemic, or a web3 native decentralized organization just starting out, propelled by revolutionary spirit.

The readings surveyed are not meant to be exhaustive or even representative. Our goal is to teach you to fish in the waters of online governance traditions for yourself. To the extent that we succeed, after reading this primer you will have developed a basic literacy around the topic, and an awareness of several major trailheads for further exploration.

While we have not entirely avoided conventional sources of wisdom on management and organizations, such as academic management literature, we have deliberately and consciously cast a much wider net. Our Year 1 readings ranged from academic papers and excerpts from classic books to corporate presentations and blog posts. We read about Paleolithic farming cultures and medieval guilds, and about modern open-source movements and platform ecosystems. We read thought-provoking bits of fiction, sampled manifestos, and even discussed essays about biology and wildlife management.

This primer does not include readings that explicitly discuss blockchain-based governance models such as DAOs. While these are both a current focus of study for our group and a possible future governance direction for the Yak Collective itself, we feel a thoughtful and critical appraisal of received traditions of governance is a necessary prerequisite for getting the most out of the rapidly emerging blockchain-focused literature. While blockchain-aware readings will likely feature prominently in a future paper, our intent here is to distill the best of the pre-blockchain past.

As we worked our way through the readings, we began developing an idiosyncratic internal lexicon for talking about online governance, drawn both from the readings and our own discussions. We believe this lexicon, a subset of which can be found at the end of this primer, has helped us level up the sophistication, immediate practical utility, and interestingness of our discussions. We encourage you to use our lexicon to jumpstart your own. We also welcome your suggested additions to ours.

The remainder of this primer is organized as follows. In the next section, we provide overview commentary on the 49 readings, organized around a conceptual map of four governance regimes. We then briefly discuss the challenges of synthesizing an online governance strategy for a particular organization from this universe of disparate, sometimes contradictory ideas. Finally, we offer some notes on our own experiences, along with suggestions for using this primer to guide your own further explorations.

We conclude with our lexicon and the annotated bibliography.

Governance Regimes

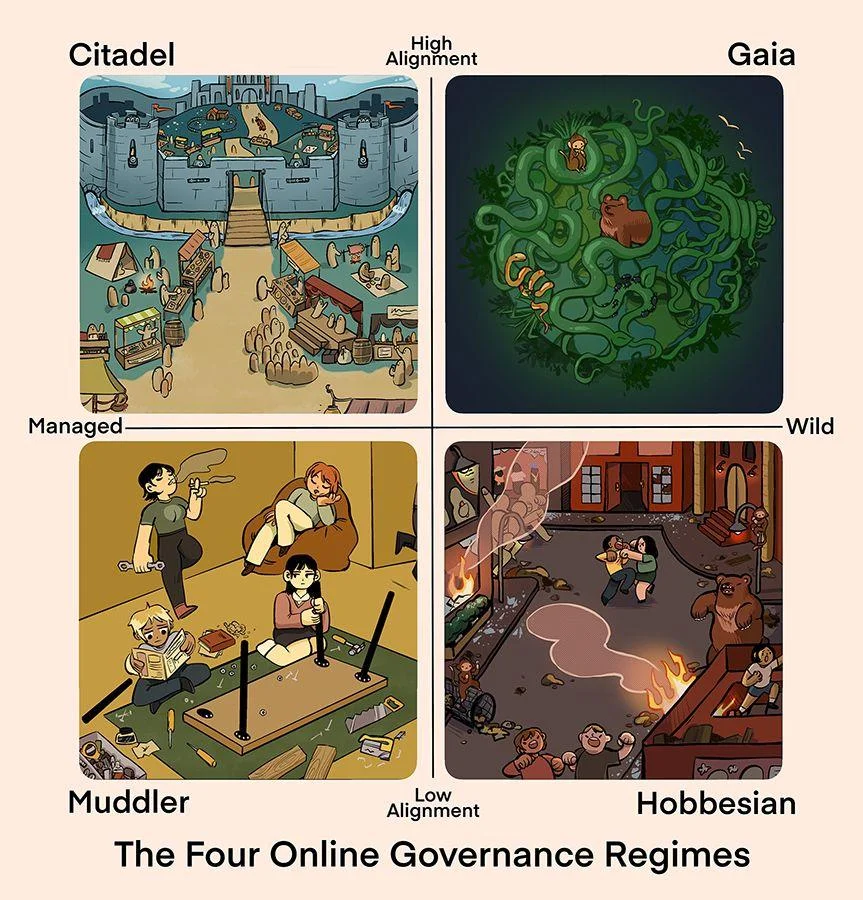

The studies in our first year led us to develop a shared map of the territory. Toward the end of the first year we carried out a six-week collaborative sense-making exercise to discuss, sort, cluster, and summarize our readings. Through that exercise we identified two principal axes that seemed the most helpful in sorting the readings:

- from low to high alignment in terms of the intentions and interests of the participants

- from managed to wild in terms of the structures and processes of interaction

The 2x2 diagram that results suggests that there are four relatively distinct regimes of online governance, which we have dubbed Hobbesian, Gaia, Muddler, and Citadel.

The Four Online Governance Regimes

In the following sections we discuss each of the four regimes in turn, roughly in order of strength of governance forces:

- Hobbesian: Governance ideas that assume wild defaults and low alignment, and attempt to foster progress despite conflict and chaos (readings 1–11)

- Gaia: Governance ideas that assume wild defaults and high alignment, and attempt to foster progress by drawing on natural patterns and harmonies (readings 12–26)

- Muddler: Governance ideas that assume managed defaults and low alignment, and attempt to foster progress by adding some process structure (readings 27–33)

- Citadel: Governance ideas that assume managed defaults and high alignment and attempt to foster progress through top-down coordination (readings 34–49)

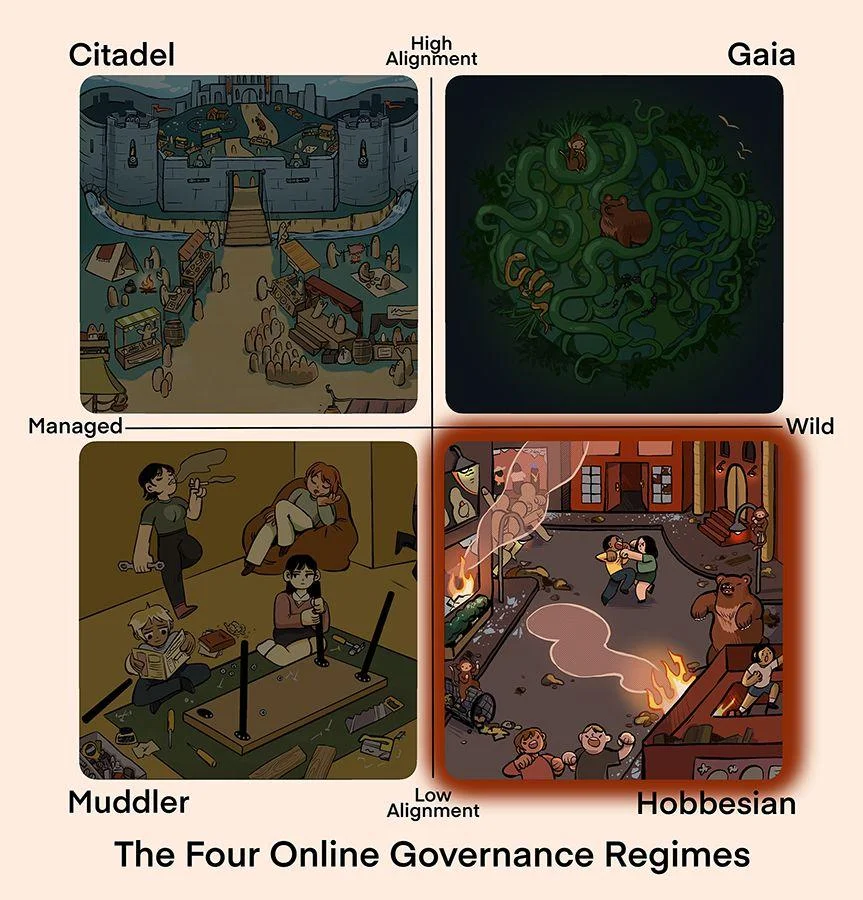

Hobbesian Regimes: Wild and Low Alignment

The Hobbesian regime, the lower right quadrant of the 2x2, is the least governed regime and can be explored through readings 1–11.

The eleven readings in this section reveal that where a group with wild defaults and low alignment has emerged and thrived, it has typically been founded by contrarians who found high-alignment cultures antithetical to their goals and personalities.

The Hobbesian governance regime is personified by the archetype of the anarch, explored in the writings of Ernst Junger [1]. The ideal anarch is an individual whose identity cannot be tied to an organization or ideology, and whose actions and principles are driven by a pragmatism that serves both him and the common good.

Hobbesian groups tend to be relatively low in energy and cohesion. As a result, a functional Hobbesian regime takes time to build and faces many risks along the way. One major risk is of individuals being isolated, scapegoated, and persecuted. Junger himself was persecuted by both the Allies and Nazis through World War II.

Hobbesian Regimes: Wild and Low Alignment

Early in its history, a wild and low alignment governance regime has to solve for trust and common knowledge. Trust is generally low among individuals who are suspicious of prevailing ideologies and exhibit an inclination towards doing their own research. Common knowledge [2] is needed for a governance regime to be functional and Hobbesian regimes typically suffer from a strong deficit.

Many online communities limit their goals to adopting tools for gathering and communicating and fail to work on building trust and common knowledge, making them vulnerable to Hobbesian failure modes. As a result, a key risk of wild and low alignment organizations is that emergent adversarial behaviors can destroy them. A symptom of such destruction in progress is the presence of multiple charismatic figures competing for influence, especially in heavily politicized contexts. The Intellectual Dark Web, QAnon, and the Occupy movement are good examples from the culture wars of the past decade.

The town of Grafton in New Hampshire [4], which was taken over by Libertarians over the last two decades, is an example of an organization that began with a goal of being in the Gaia quadrant (wild and high alignment) but turned Hobbesian due to lack of alignment with existing residents of the town. Unmanaged emergent effects—bears running amok in Grafton’s case—can be traced to insufficient levels of institutionalized common knowledge.

A more enlightened way to handle Hobbesian conflict might have been to take the approach of Musical.ly founder Alex Zhu [5] who analogizes joining a new social network to moving to a new city—“come for the utility, stay for the community.”

Hobbesian patterns of governance tend to work during the early years of a subcultural scene or organization, but tend to fail as they scale. David Chapman [6] attributes this to an invasion of people seeking social status, or worse, seeking to exploit the chaos for personal gain. This particular pattern of hostile entryism in young Hobbesian organizations or scenes has co-evolved rapidly, over the last century and a half, with technologically mediated mass culture. Anarchists in early 20th-century China, for example, were infiltrated by communists operating within a more effective top-down structure [7]. Operating relatively under the public radar (a strategy sometimes called security through obscurity) can help protect a Hobbesian group from being overrun by sociopaths or invading ideologies.

One way to mitigate such effects is to simply eschew growth and the hierarchical structures it tends to induce. Contemporary organizations have inherited the twentieth-century bias toward growth for the sake of growth, typically measured through metrics such as number of members, revenue, and impact on the zeitgeist. Eschewing growth, however, comes at a cost. Nonhierarchical cultures tend to be poorer, as Sarah Constantin [8] points out in an essay on the relationship between hierarchy and wealth. Hierarchy is expensive because it requires systems and people to manage it. It also tends to incentivize the creation of wealth to pay for itself.

Emerging forms of nonhierarchical organization could potentially offload many of the traditional functions of hierarchical structures to low-cost automation, allowing relatively Hobbesian organizations to cohere and persist at larger scales. Web3 technologies such as DAOs are a development worth watching in this evolutionary direction.

Hobbesian regimes work sustainably if individuals manage to arrive at a high level of shared common knowledge and a shared understanding of the common good before they are undermined by the many risks. More commonly, however, they transition to one of the other three regimes depending on which internal dynamics predominate:

- If a Hobbesian organization produces enough common good that effective ongoing management is induced, it starts to have the characteristics of an organization with Muddler governance characteristics.

- Where charismatic influence drives higher alignment, a Hobbesian group can transform into one with Gaia governance characteristics.

- Where a more organized, hierarchical group invades and takes over at the top, it can turn into a group with Citadel governance characteristics.

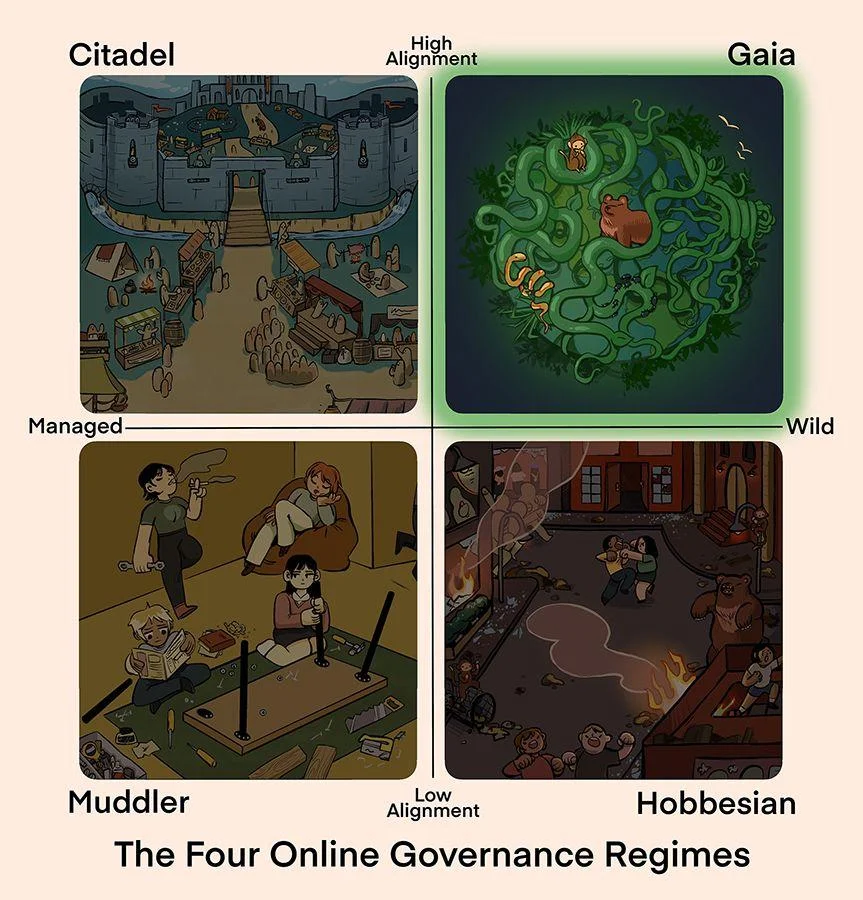

Gaia Regimes: Wild and High Alignment

The Gaia regime, the upper right quadrant of the 2x2, is the second-least governed regime and can be explored through readings 12–26.

Gaia, the Greek goddess who personified the Earth, also personifies the fifteen readings in this section. The goddess Gaia was the inspiration for James Lovelock’s Gaia Hypothesis [12], which holds that living things adapt to and transform their environments. Lovelock speculated that the complex process of wild coevolution implies that ecosystems are always optimizing for the continued existence of life. Groups of people who gather in pursuit of a common goal with wild sensibilities can be said to constitute a Gaia governance regime.

The overarching governance question in a Gaia regime is this: will the strong tendency toward organic coevolution make the organization resistant to any form of designed structure, even when it improves functioning or addresses possibly fatal weaknesses? In contrast to the Hobbesian regime, which shares the basic suspicion of formal structure, the presence of high alignment makes different outcomes possible.

Gaia Regimes: Wild and High Alignment

It is important to understand the distaste for designed structures that drives organizations in the Gaia quadrant. Ivan Illich, arguably a Gaian philosopher, exhibited a particularly refined form of this distaste. Illich’s work was marked by a tension between progressive, libertarian, and anarchist impulses.

Dave Pollard offers an accessible overview in his post, Ivan Illich: The Progressive-Libertarian-Anarchist Priest [13]. Illich’s work can be understood as a response to the designed institutions which make up modern societies, especially in fields like education and medicine. These institutions are a result of the drive to organize large groups of specialists in industrial modes, with a narrow focus on metrics such as productivity. But there is a dark side to this process: the progressive erosion of individual dignity.

Jerry Pournelle’s Iron Law of Bureaucracy [30] suggests that industrial-mode institutions are doomed to eventual capture by cults of expertise, which leads to cartel-like organizational behaviors. Complex education and training pipelines emerge, to sustainably produce the narrow specialists needed to perpetuate the captured condition. The result is progressive loss of dignity for all participants.

In an effort to reclaim their dignity, individuals often gravitate to anarchist ideas as a response to the burdens of institutional life. Jo Freeman’s essay The Tyranny of Structurelessness [31] outlines what can happen next. First, informal structures will emerge, with unclear norms and unwritten rules. The authority within the group will be concentrated to a select few elites and status games will ensue as individuals in the group jockey for position. Once this happens, the group loses focus on its original goals, making progress next to impossible.

The challenge of the Gaia governance regime is to overcome both the tyranny of systems of control and the tyranny of structurelessness. If individuals can agree on both the mission and the means of accomplishing that mission, they can then decide if they’re willing to give up a certain amount of freedom in order to reap the benefits of being in the group. This alignment is often achieved through a temporary period of charismatic leadership, though such leadership risks becoming a benevolent dictator for life [36].

The most important task in governing a Gaia organization is to clearly define measures of success in a way that manages the tension between the goals of individuals and the goals of the organization. When the tension is too great, imbalance threatens the stability of the organization. Another advantage of defining the measures of success is that it provides a simple criteria to filter potential additions to the organization. Once everyone has an idea of what success looks like, it is possible for individuals to understand how they fit into the bigger picture.

The case of Morning Star, a large tomato processing company, illustrates what wild and high alignment conditions look like [14]. Each Morning Star employee creates a colleague letter of understanding (CLOU) which outlines their personal responsibilities and means for being held accountable. Their CLOU is renegotiated every year. Each person in the company gets an opportunity to define how they contribute to the company’s success.

Transparency is a key enabler in Gaia governance regimes. GitLab [15] models itself after open-source software projects. With employees distributed across the globe, the company has to impose some structure to induce order in the chaos. The GitLab employee handbook stresses the importance of documenting decisions, communicating in public spaces, and breaking work down into the smallest pieces possible. Combined, these elements provide individuals with a holistic view of the company’s operations and their own role within it.

Gaian organizations are sensitive to the limits to structure. Things will not always work as intended. Even the most aligned teams will have dissent. In their famous “culture deck,” Netflix [16] recognizes this and provides employees with a process for resolution: they must be willing to voice their dissent and be able to articulate why they disagree. An informed captain then reviews the issue from all sides and makes a decision. This captain, who often will have to tease out these frustrations, documents the decision for review by the entire organization. Captains are trusted to make informed decisions and don’t need consensus to move forward. The team is expected to rally around the final decision so that the outcome is as successful as possible.

Gaia governance regimes tend to discriminate against candidate members who don’t have a shared understanding of organizational values. In their Handbook for New Employees, Valve [17], for instance, asserts that their Gaia model is scalable, as long as they remain particular about the people they add to the company. Making the wrong hire can be a particularly expensive mistake in Gaia regimes: either you let a promising potential hire get away, or you miss key warning signs and a new team member wreaks havoc on the organization.

Many general principles are revealed by these specific cases. Gaia organizations delegate tasks and authority and demand strong commitment from individuals in return. With such delegation come responsibilities for meeting criteria for success. Over time, individual responsibilities must be switched around to avoid the hoarding of knowledge. Information must be made freely available. All decisions must be documented to provide context to the rest of the team.

When these principles are successfully adopted and practiced, organic coevolution is possible, and the system can operate with high energy and tempo. Where they fail, Gaia organizations can drain energy and migrate into the Hobbesian quadrant, through unmanaged dissent and unraveling alignment. Or they might lose variety and distributed autonomy, adopt stronger, more overt organizational forms, and move into the Citadel quadrant.

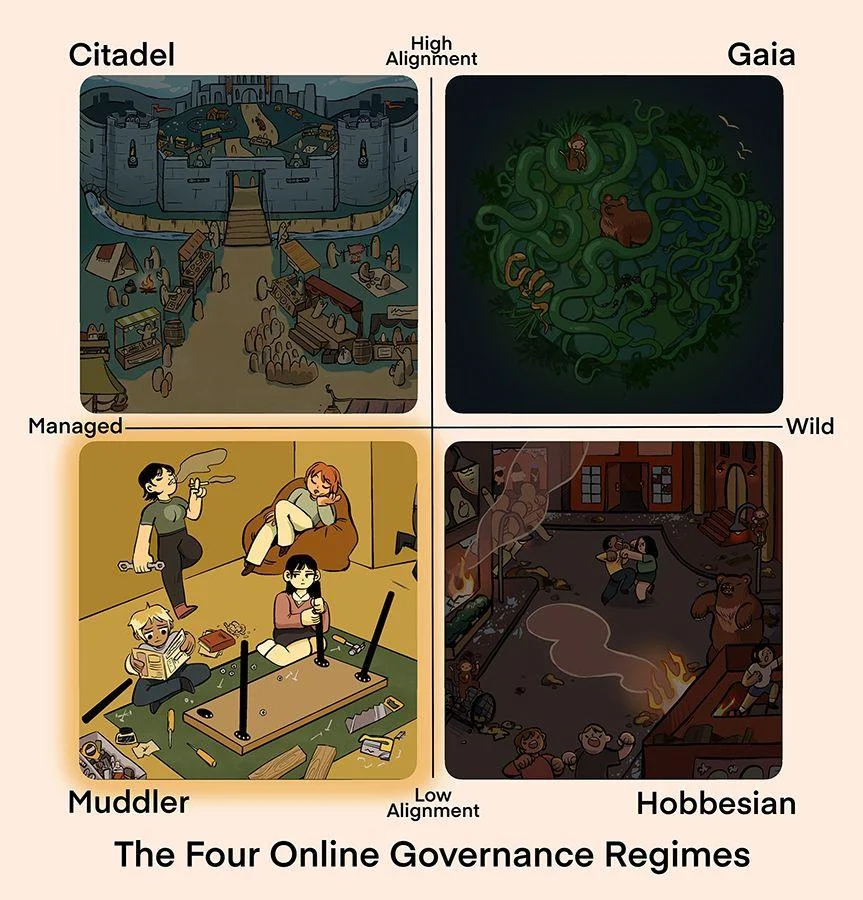

Muddler Regimes: Managed and Low Alignment

The Muddler regime, the lower left quadrant of the 2x2, is the second-most-governed regime and can be explored through readings 27–33.

The Muddler governance regime represents a condition of shared and commonly acknowledged ignorance rather than common knowledge, with expectations set accordingly. The critical insight regarding the Muddler regime is that self-deprecating humility and a sense of humor in approaching decentralized orgs is a superpower.

When a group sees itself as ordinary people muddling through in ignorance, doing their mediocre best rather than as Chosen Ones constructing a utopia, things are seen in realistic proportions. The seven readings of this section help foster and anchor the attitudes necessary to govern in the Muddler regime.

Muddler Regimes: Managed and Low Alignment

The quadrant label comes from Charles Lindblom’s 1959 article, The Science of Muddling Through [27]. In it, Lindblom identifies the method of successive approximations (which bears a strong resemblance to modern agile management methods) as a characteristic of successful organizations. The muddling-through organization is the opposite of the efficient, machine-like organization. Frederick Laloux [28] characterizes this condition in terms of loosened optimality criteria, and heightened appreciation for the benefits of “fatter” unoptimized systems. An example can be found in the interview with Tobi Lüttke, founder of Shopify [29]. The key is understanding the organization as a complex system, and being non-deterministically in harmony with, and attuned to, what’s going on. But this posture must also be oriented toward a purpose, and resist simply surrendering to the system’s natural evolutionary tendencies.

You can tell you’re in the Muddler quadrant if you seem to be making progress, but in a confused, near-random-walk way, with many misunderstandings between people due to misalignment at the level of information rather than values. Over time you notice net positive movement emerging. Forbearance and patience achieve a lot. There is a sense of inefficient and sloppy relentlessness. Knowledge retention and transmission will be lossy, naturally producing the muddling-through process and killing any attempt to do a rational planning process.

A key risk in the Muddler quadrant is bureaucratic capture. Jerry Pournelle’s Iron Law of Bureaucracy [30] and Jo Freeman’s Tyranny of Structurelessness [31] both argue that “management” effectively emerges, for better or worse, even if things look unmanaged. Anarchy in the sense of chaos is unstable.

The tempo of the muddling-through regime—staccato stop-go janky progress—is captured by two short readings. The Hurling Frootmig principle—derived from a passage in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy [32]—states that most work gets done by random people wandering in at lunchtime and seeing something worth doing. The Wind in the Willows principle [33] asserts that people can vanish abruptly and reappear at any time, and that the system should be able to make use of their unpredictable availability anyway. These two principles suggest a key tension between being, on the one hand, open to the serendipity of creative contributions from unexpected new participants and, on the other hand, forgiving of unreliable and unequal participation by existing participants caused by the uncertainties and resources limits of individual lives. This idea harmonizes with what’s become known as Postel’s Law, from The Tao of the IETF [35], which advocates, “be conservative in what you send and liberal in what you accept.” Applied to governance, muddling through requires being conservative in what you police and liberal in the patterns of participation you accept.

Muddling through is a low-energy condition because there is a lot of acknowledged uncertainty and decisions/actions happen despite this uncertainty. Time is spent in experimentation and rework, as well as in sorting out tactical confusions and dealing with shifting patterns of participation.

At the Yak Collective, the Muddler regime tends to be the default quadrant. Other quadrants are inhabited by exception. For example, within a well-defined project we might drive up to Citadel or Gaian levels of energy or alignment; around a contentious issue we might briefly inhabit the Hobbesian quadrant. But much of the time we are muddling through.

What makes the Muddler regime a stable place is that things actually tend to live up to expectations based on good-humored cynicism. The challenge, though, is that these expectations are typically low. The Muddler regime can yield somewhat desultory, stop-go progress. Without spikes of more energized action, staying permanently in a Muddler regime can equal a slow death.

Citadel Regimes: Managed and High Alignment

The Citadel regime, the upper left quadrant of the 2x2, is the most strongly governed regime and can be explored through readings 34–49.

The sixteen readings in this section revolve around organizations that are usually discussed in terms of platforms and ecosystems.

Platforms and ecosystems are ubiquitous today, but are still confusing even for their participants. An ecosystem can be defined as “a dynamic group of largely independent economic players that create products or services that together constitute a coherent solution” [20]. The significant questions in the Citadel quadrant revolve around why and how exactly these independent players can collaborate, what keeps them together, and how their products and services compete.

Citadel Regimes: Managed and High Alignment

One of the problems most platform builders face is that intuitions developed while running a traditional organization frequently fails them. For example, hoarding power and value is often adaptive in traditional organizations but can drive platforms to failure. Intelligent ways to distribute power and value can be hard to discover.

Metaphors derived from traditional organizations can be misleading as well. For example, the name Citadel selected for this governance regime, while generally reflective of the underlying aspirations, implies strong walls to protect an ecosystem or a marketplace from external threats. While the metaphor highlights some of the logic of this regime, it misses a key point. Ecosystems and marketplaces need dynamic, rather than static, protection. It is their openness that makes them stronger. What needs protection might be an economic engine defined via network effects, rather than a geographic perimeter or traditional market boundary. It may not be possible to hide such an engine behind walls. And unintended consequences from network effects can break even the strongest of walls.

Threats can also emerge internally in a citadel ecosystem. For example, there is a tension between attempts to ensure that hierarchical control is tractable and the need to respond to novel circumstances in novel ways, leading to the proliferation of new rules, new teams, and unconventional ways of working.

These forces operate at different tempos. Hierarchical forces operate on linear time scales, according to designs and plans. Emergent ones operate on a more organic tempo, characteristic of the the organizations discussed in the Gaia quadrant. These emergent forces are typically weak in the beginning, but can strengthen rapidly as the organization learns. Uneven tempos are a feature, not a bug, but the hierarchical regulation forces that they trigger can fail by being too slow or too fast. The most likely outcome of such misregulation is a ghost town, where serendipity has been squashed.

When this tension is palpable, it is a clear sign that you’re in the Citadel quadrant. It is precisely this tension that produces ecological surprises. An ecological surprise is a turn of events that can’t be predicted based on traditional logic. This happens when people are either wrong about the future, mismanage the system, or discover something surprising about it.

Surprises are inevitable. You can either fight them or learn from them. Some organizations successfully turn this process of constant discovery into an element of their economic engines. In such cases the creative tension drives what can be called “a serendipity engine.” An example is the Pinduoduo marketplace [34]. Individuals with well-developed platform thinking mindsets are able to see most surprises in a serendipitous light. But for people with strongly traditional hierarchical mindsets, every surprise can seem like a threat.

Ecosystem governance is about nurturing and protecting network effects by responding appropriately to surprises. But there are few universally applicable governance principles. Due to winner-take-all effects, every successful example tends to be one-of-a-kind. Lessons from specific examples tend to be hard to generalize.

As a result, attempts to accurately describe what’s going on inside a sufficiently developed citadel ecosystem usually fail. You can, of course, study the principles sincerely articulated by insiders, but they are difficult to port to other settings.

Principles derived from successful examples like the IETF (an organization with both Citadel and Muddler characteristics), make complete sense only in the context of the original circumstances. Furthermore, these circumstances are not static, but change with the development of an ecosystem. For example, the authors of The Tao of the IETF [35] acknowledge that the principle “the IETF recognizes leadership positions and grants power of decision to the leaders, but decisions are subject to appeal” only makes sense in the context of specific historical details, but the details themselves are meaningless to outsiders, making the principle hard to port to other contexts.

Due to the uniqueness of successful platforms, the only general principles available are broad-strokes ones. One such principle can be found in a speech delivered in 2014 by Frank Chimero [36].

In it, Chimero contrasts the cases of managing wolves in farming regions of the Western United States and managing bear populations within Yellowstone National Park. In the former case, which played out early in the history of the region, the interests of the organized ranching industry led to a failed attempt to manage the wolf population through large-scale slaughter, aimed at eradication. In the latter case, a similar problem involving the bear population was successfully addressed through investment in long-term sustainable population management processes. Chimero uses the two cases as motifs of two very different approaches to problems in complex systems emerging from the collision between structured interests and wild ecosystems: “shooting the source of the problem” versus “investing in a process to keep things open and adaptable.“

This is perhaps the essence of managing Citadel-like systems that attempt to create islands of order and civilization within essentially wild ecosystems.

The Synthesis Challenge

We see two primary challenges in designing an online governance strategy for an organization.

The first challenge is to introspect on levels of alignment and management capability to identify the prevailing regime and adopt appropriate mental models, reference precedents, and heuristics. Trying to run a citadel-like environment with a Hobbesian approach, or vice versa, is a recipe for disaster.

Assessing any organization, especially a young one with poorly developed characteristics and a short history, is a highly subjective exercise. Our studies suggest that paying attention to three key attributes can help locate organizations in the vast space of possibilities and orient toward the most important problems and potential challenges: temporality, energy, and common knowledge:

- temporality: the seasons, cadences, events that are unique to the group or organization

- energy: the energy level of the group, which shapes the type of projects and work it will engage in

- common knowledge: the shared knowledge in the organization

While the four regimes and associated readings from the previous section provide a starting point for modeling any online governance situation, we recognize that all such taxonomies are arbitrary. No organization is purely in one regime or the other or stays in a stable location. No taxonomy can capture all the salient features of a particular situation. The two axes that we have chosen for our framework—alignment and management—may not foreground the most important aspects in a particular case.

Developing appropriate mental models for the unique circumstances of a given organization requires imagination. We hope the framework and readings we have introduced provide you with good fodder and a starting point.

The second challenge is to avoid common traps. In our studies and discussions of various cases, two traps stood out in particular:

- over-indexing on technology and

- over-indexing on traditional institutions.

Over-indexing on technology, driven in part by the sheer excitement around new technologies, leads to what we’ll call the techno-utopia trap.

Many who participate enthusiastically in online communities approach online governance as though the mere use of the newest media—whether it is messaging apps or blockchains—changes almost everything, creating a blank slate where ideal visions of organization can be realized. To the extent historical experiences (including older online experiences over the past forty years) inform or inspire governance ideas at all, they tend to do so in the form of biases inherited from particular romanticized historical eras favored by early members of a given community. Favored historical reference points include medieval guilds, the Hanseatic league, 60s counterculture, and early 90s USENET culture.

While this blend of tabula rasa thinking and romantic cherry picking of reference points can occasionally lead to refreshing new insights and much-needed shedding of historical baggage, it can also lead to naive idealism and wishful thinking, and governance attempts that fail through inevitable disillusionment.

Over-indexing on traditional institutions, driven in part by the sheer abundance of scholarship and historical information about them, leads to what we call the grand-old-institution trap.

Those invested in long-running traditions of scholarship and research relating to questions of governance and management (often from academia) often approach the question as though the context of new digital tools, information ubiquity, algorithmic mechanisms, and unusual patterns of organizing changes almost nothing. Such individuals often have limited experience of deep, extended, skin-in-the-game participation in online, virtual groups. They often assume that any new governance principles can be inferred through relatively shallow “field research” in a conventional anthropological mode, coupled with the application of well-known ideas. Perhaps most importantly, they are often blind to the biases they inherit from their own home institutional forms such as universities, corporations, nonprofits, or public sector institutions.

While such a tradition-bound approach can occasionally cut through simplistic utopian thinking and introduce much needed sophistication to active online governance efforts, it can also lead to entirely missing the essence and power of online modes of gathering, organizing, and doing. The result is often governance attempts that fail through lack of imagination.

Online governance is a challenge where “the medium is the message” effects are particularly strong, and tradition casts a very long shadow. This makes organizational synthesis a wicked problem at the intersection of tradition and technology. New technologies might offer powerful and novel affordances in one area, while rendering familiar ones unworkable. Old traditions might bring much-needed thoughtfulness in one area, while crippling the potential of new technologies in another.

Synthesizing an effective governance strategy in the face of these challenges is not easy. The principals must cultivate imaginative mental models that embody inspiring, generative, and elegant ideas, as well as an aliveness to practical concerns, historical baggage, and well-known risks that can derail attempts to actually execute on them. The cost of failure is wasted time, energy, and resources, but the reward of success is that your organization just might inherit the future.

Conclusion

For the Yak Collective, the ideas we have surveyed in this primer are not mere stimulating fodder for intellectual curiosity. They shape our own ongoing attempts to govern ourselves better and do more things, and more interesting things, both individually and collectively.

The current broad mission of the Yak Collective is to create an online network and community for collaborating on independent projects in a welcoming, friendly context. Our mission continues to evolve, guided by our ongoing studies and the needs of our latest projects. Week by week, we continue to muddle through, with periodic excursions into Hobbesian, Gaia, and Citadel regimes. Currently we are exploring how to adopt web3 technologies in creative ways and pursuing ambitious projects in other areas.

Our own studies and readings continue in our weekly online governance meetings which are free and open to all our members. You are welcome to join us. You are also welcome to reach out for help and consulting support for your own online governance challenges.

You can join the Yak Collective here. The online governance chats happen on our Discord server Fridays at 11 CST (UTC-6).

Suggestions for Next Steps

The format of this primer is loosely inspired by the format used at Amazon meetings—the well-known Amazon 6-pager. If you are part of a group or organization learning to govern itself online, we highly recommend reading this paper as intended—in a small group of 8-10 and at the start of a meeting to discuss it. Allow about 20 minutes for a quick first read. If you’re interested, reach out and one of us will be happy to join you for your session.

We believe the primary value of this document lies in our lexicon and the curated list of readings. To get the most out of it you should at least browse the lexicon and sample a handful of the readings.

We recommend the following lighthouse readings as being particularly valuable since they articulate foundational ideas:

- Jo Freeman’s The Tyranny of Structurelessness [31]

- Charles E. Lindblom’s The Science of Muddling Through [27]

- Steve Yegge’s Platform Rant [37]

- Donna Haraway’s Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene [23]

Lexicon

Birds of a Feather: People with the same interests who might do things together. From glossary of The Tao of the IETF.

Best Current Practice: A type of request for comments (RFC), a documentation of the best way to do something.

Clark Principle: “We reject kings, presidents and voting. We believe in rough consensus and running code.”

—David Clark, from The Tao of the IETF.

CRiSP: “continually regenerating its start position”—a form of governance embedded within the idea of an open participatory organization. A learning organization that reproduces itself. From Bonnita Roy’s Open Architecture for Self Organization.

Decentralized Control: A system of governance in which there is no single member has overall control of resources or decisions. Principle from The Tao of the IETF.

Dynamic Capability: “[T]he firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments.”

—David J. Teece, Gary Pisano, and Amy Shuen

Dogfooding: Eating your own dogfood is the practice of an organization using its own product. From Steve Yegge’s Platform Rant.

Eedies: Player types that can do damage to a guild. Notable examples are the Greedy, the Needy, the Leety, and the Cheaty. From Nonhuman Resources: Recruiting Players and Evaluating Recruits.

Yak-Etiquette: “Mole recollected that animal-etiquette forbade any sort of comment on the sudden disappearance of one’s friends at any moment, for any reason or no reason whatever.”

—Wind in the Willows

(see also: Postel’s Principle)

Edge-User Empowerment: A principle in the IETF that edge users of the internet should be empowered; can be generalized to any decentralized system. Also applied to devices at the edge (or client end) of the network. Applied to the Yak Collective, implies prioritizing individuals attached to the edge of the social graph—e.g., new members just joining or people who occasionally participate in small ways—over those at the core who are heavily involved. Principle from The Tao of the IETF.

Externalizable: A means of characterizing service interfaces designed for more public and externally oriented forms of consumption; often implemented through a broad set of case-specific rules. From Steve Yegge’s Platform Rant.

Fault-Tolerant Byzantine Sharding: “I realize I’ve been unconsciously operating with this heuristic for a while. I am going to try and make it more rigorous. Something like ‘it should always take minimum 3 people to construct a global state snapshot even approximately, and there should be no MECE subgroup… any group with global state awareness should also have minimum 2x redundancy. For example, if there are 3 logical bits in a state, p, q, and r, and 3 people, A, B, and C, who each know max 2 bits, you can have: A knows (p, q), B knows (q, r), C knows (p, r). The full state is known with 2x redundancy by the group.’ I’m guessing there’s an infosec or distributed computing idea like this. If not, I’m calling it fault-tolerant Byzantine sharding.”

—Venkatesh Rao on the Yak Collective Discord

Flash Teams: Flash teams advance a vision of expert crowd work that accomplishes complex, interdependent goals such as engineering and design. The goal is to enable experts and amateurs alike to contribute skills they enjoy, on a set of tasks that they find interesting, and at scale. Flash teams require small atomic actions called blocks. Flash teams exhibit distributed leadership. From Expert Crowdsourcing with Flash Teams.

Free Rider: Classic economics concept pioneered by Mancur Olson. It refers to people who make use of public goods without contributing to their upkeep and renewal. Related to Tragedy of the Commons. From Wikipedia.

Hurling Frootmig Principle: Things are best done when random people wander into workplaces at lunchtime when actual employees are out to lunch. From The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

Iron Law of Bureaucracy: There are two types of people in an organization—people who are dedicated to the goals of the organization and people who are dedicated to the organization itself. The Iron Law of Bureaucracy is that people who are dedicated to the organization will eventually take control of it. From Iron Law of Bureaucracy.

Land-Grab Mode: Once there is minimum viable happiness and tipping loops in marketplaces, look for other opportunities that are adjacent to the values of the brand/community. From Hierarchy of Marketplaces.

Leety: Players that treat themselves as elite. Think that they have to win every argument no matter how trivial. From Nonhuman Resources.

Library-shelf system: A form of common knowledge where organizational functionality is maintained as self-contained and interoperable packages. From Steve Yegge’s Platform Rant.

Murmuration Principle: Ad hoc groups form, move, and disperse as needed to feed and evade predators. An individual can make good decisions for the group with situational awareness of a few other nearby individuals. From An Open Architecture for Self-Organization.

Minimum Viable Happiness: Platforms that create meaningfully more happiness in the average transaction than any substitute, not how many transactions you accumulate, will dominate the market. From Hierarchy of Marketplaces.

Muddling Through: An approach to decision-making based on successive limited comparisons. Compare Rational-Comprehensive. From The Science of Muddling Through.

Postel’s Principle: “Be conservative in what you send and liberal in what you accept.” From The Tao of the IETF.

Platforms: An underlying basis of operations from which functionality is executed, often through a service interface. From Steve Yegge’s Platform Rant.

Platform Business Models: A process of creating value by an array of players whose specific roles and responsibilities are geared toward generating and sustaining network effects. From A Systemic Logic For Platform Business Models.

Rational-Comprehensive: Also called the root method. An approach to complex decision-making based on logical root-cause analysis and comprehensive modeling. It is contrasted to the method called muddling through or the branch method, from Lindblom’s The Science of Muddling Through (see Muddling Through). In general, the branch/muddling through/successive limited comparisons method is preferred by the Yak Collective and the root method is only appropriate in limited bounded problem domains where comprehensive perfect information is available. From The Science of Muddling Through.

Service Interface: A means of exposing knowledge or functionality independent of underlying operations in a fashion that accounts for user accessibility. From Steve Yegge’s Platform Rant.

Service-Oriented Architecture: A style of designing systems where component pieces are wrapped in service interfaces such that they are self-contained, interoperable, and repeatable. From Steve Yegge’s Platform Rant.

Slime Mold Principle: Creating affordances for simple exploratory behaviors in a group leads to fruitful developments. “There is nothing magic that humans (or other smart animals) do that doesn’t have a phylogenetic history. Taking evolution seriously means asking what cognition looked like all the way back. […] From this perspective, we can visualise the tiny cognitive contribution of a single cell to the cognitive projects and talents of a lone human scout exploring new territory, but also to the scout’s tribe, which provided much education and support, thanks to language, and eventually to a team of scientists and other thinkers who pool their knowhow to explore.” From Cognition all the way down.

Successive Limited Comparisons: An approach to complex decision-making, also called muddling through or the branch method, based on Lindblom’s The Science of Muddling Through (see Muddling Through) that relies on systematic trial and error starting from limited, local solutions to a larger problem. Contrast with the root method. From The Science of Muddling Through.

Theory of the Firm: An approach to economics pioneered by Ronald Coase, based on the idea that firms emerge when internalizing activities within an organizational boundary minimizes coordination and transaction costs.

Tipping Point: Point at which the core goal of the platform or community becomes easier and not harder. For a marketplace platform this could mean lower acquisition cost, doing fewer non-scalable things. Tipping loops are happiness loops + loops related to growth of the platform (e.g., for the Yak Collective it is the number of projects active/in pipeline, etc.). From Hierarchy of Marketplaces.

Tragedy of the Commons: Classic game-theoretic formulation of the problem of too many people making use of public resources and too few contributing to its upkeep. Often used as the explanation for why public goods get appropriated for private benefit over time and often modeled with the prisoner’s dilemma game. See also Hurling Frootmig Principle which is a sort of reverse tragedy of the commons.

Versioned-Library System: A form of maintaining common knowledge where the state of common knowledge and state changes are kept track of through an incrementally increasing naming heuristic. From Steve Yegge’s Platform Rant.

Weber’s Iron Cage: Peer Production (communities, open source projects) is generally seen as a utopian upgrade to bureaucracy but as complexity of peer production grows, peer production could also become similar to bureaucracy. From The limits of peer production.

Yak: A large bovine native to the Tibetan plateau.

Annotated Bibliography

- Ernst Junger: Core ideas of Ernst Junger. The anarch can take any form, does not actively resist tyranny, is pragmatic, and sees what can serve him and the common good, but is closed to ideological excess. ⮨

- Common Knowledge Problem: Working in groups requires common knowledge to be built and dissipated across time. New members find it harder to join a group when they don’t have the common knowledge of the rest of the group. ⮨

- Nakatomi Space: Breaking out of common understanding of barriers and standard processes enables greater degrees of freedom toward achieving a desired goal or outcome. Principle explored via an architectural close-reading of the movie Die Hard.

- The Town That Went Feral: Libertarians flock to small New Hampshire town to live as they please, but the lack of organization and alignment made life worse for all. ⮨

- Notes on Interview with Alex Zhu: It is very hard to change human nature. We should follow it instead of fighting with it. “Come for the utility, stay for the community.” ⮨

- Geeks, MOPS, and sociopaths in subculture evolution: Subcultures are subject to forces that put them on a predictable trajectory, which can be managed if the subculture is willing to see their thing for what it is and Be Slightly Evil to defend what is good. ⮨

- Anarchists in China: A history of the Chinese anarchist movement in the 1900s with strong parallels to current times. This movement coincided with late stage industrial revolution, and surfaced tensions between individual freedom and a uniform moral code that is imposed top-down. ⮨

- Relationship between hierarchy and wealth: Structurelessness in organizations is hard to maintain. There are examples of stateless anarchies which possibly built bronze-age level cities in Iceland, Harappan civilization, etc., but there are no examples of it in industrial societies. Hierarchy is expensive, more freedom causes poverty. ⮨

- The Limits of Peer Production: The authors take a skeptical view of utopian claims about the vision of peer production and argue that it has less revolutionary potential than claimed, and requires more critical scrutiny. They see it primarily as an extension of existing modes of production, with all the baggage that entails.

- Doctorow Metacrap article: Barriers to making useful metadata (c. 2001).

- Picking the Right Approach: About trust and common ground: There are a lot of tools being developed for collaboration but many of them don’t solve the problem. The main problem seems to be lack of knowledge about where the expertise lies and how to find it.

- Gaia Hypothesis: James Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis proposed that living organisms interact with their inorganic surroundings on earth to form a synergistic and self-regulating, complex system that helps to maintain and perpetuate the conditions for life on the planet. ⮨

- Ivan Illich: The Progressive-Libertarian-Anarchist Priest: Blog post by Dave Pollard. “Institutions create the needs and control their satisfaction, and, by so doing, turn the human being and her or his creativity into objects. Illich’s anti-institutional argument can be said to have four aspects: a critique of the process of institutionalization, a critique of experts and expertise, a critique of commodification, and the principle of counterproductivity.” ⮨

- Morning Star’s Success Story: Self-managing principles of worldwide market leader in tomato processing. Uses a format they call the Colleague Letter of Understanding (CLOU)—a short document that details an employees’ personal commercial mission and all the commitments they have made with employees who are affected by their work. All employees also go through an onboarding process which seems to involve unlearning previous habits. ⮨

- GitLab’s Approach to All-Remote: A whitepaper examining GitLab’s asynchronous work model and the main practices that are implemented to create an effective environment for work. Primary thrust seems to be premised around a strong shared culture of self-contained, legible communications and how operational autonomy can be attained at the cost of lower strategic autonomy a la modeling workflows after CI/CD. ⮨

- Netflix Culture Deck: Netflix deck on being an individual contributor without a lot of centralized management and avoiding chaos with increasing complexity. Key tenets include functioning like a pro sports team, and operating in highly aligned loosely coupled ways. ⮨

- Valve Employee Handbook: Valve, the video game studio, provides principles for employees to operate without managerial oversight. Topics include choosing projects, performance reviews, self-improvement, and growing the company. ⮨

- Ingroup Contrarian: Assuming a Durkheim-Girard approach to analyzing group dynamics in terms of mimesis and effervescence, this article explores the phenomenon of the scapegoating of the ingroup contrarian.

- Free-rider problem: Classic principle (Mancur Olson) of collective action that develops a model of free-riding behavior in primarily a game-theoretic way as a problem to be solved.

- Do you need a business ecosystem?: The authors defined a business ecosystem as “a solution to a business problem, as a way to organize in order to realize a specific value proposition,” and aimed to flesh out that definition by examining how it differs from other governance models, basic types of business ecosystems when it is an effective governance model and the associated drawbacks. ⮨

- Technology, Innovation, and Modern War: Examined the ways new operational or organizational doctrines are created, and the factors that contribute to the timing of such a change. Especially in the public sector, doctrinal changes are aimed toward gathering buy-in from a large bureaucracy of politically motivated executives. When implemented from the top-down, such directives are at risk of being out of touch with the realities of those on the front line. This divergence then causes innovative pressure to build from the bottom-up in the form of hacked together solutions, and when the tension is no longer sustainable conditions become ripe for an organizational sea change.

- Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction: Ursula Le Guin claims that fiction is predominantly hero-centric: it begins with struggle and ends in triumph or tragedy. But she also believes that there’s another way: telling the stories of ordinary people instead of heroes, which we can store in our own containers to reflect upon in the future.

- Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene: Donna Haraway proposes an alternative concept of the anthropocene called the Chtuhlhucene, based on a local-global entanglement with nature, and contrasts the concept with the Lovecraftian cosmic-horror version of Cthulhu (different spelling, same Greek root inspiration). ⮨

- Introduction to Kropotkin: Kropotkin wanted to base anarchist theory around biology—the idea that animals have a higher chance of survival by collaborating than being competitive. His ideology was reactionary to the growth of centralized governance. His theory was that “mutual aid” was responsible for the growth of mankind till the medieval ages when centralized ideas such as that of the church and state started to take hold.

- Hoe Culture: Hoe culture maximizes production per hour of labor, and is not physically demanding. This leaves lots of time for leisure, and also enables women to be economically productive and enjoy other freedoms. Plow culture maximizes production per unit of land, which has historically required the strength of a man to quickly turn over fields. Men support women, and culture becomes deferential to the producers. The author makes no claims of right and wrong, but uses this model as proof that non-patriarchal societies have worked in the past.

- Cognition All the Way Down: Authors look at parts of organisms as agents, detecting opportunities and trying to accomplish missions. They admit that it can be risky, but it is a worthwhile thought experiment. “Treating cells like dumb bricks to be micromanaged is playing the game with our hands tied behind our backs and will lead to a ‘genomics winter‘ if we stay exclusively at this molecular level.”

- The Science of Muddling Through: Charles E. Lindblom contrasts two methods for working through complex, messy problems: rational-comprehensive or root method, and successive limited comparisons or branch method. The latter is muddling through. He argues that the latter is both more effective and more used in practice. ⮨ ⮨

- Frederic Laloux on what lies ahead for business: Platforms and ecosystems are more robust in turbulent times but can become fragile when everything is steady. ⮨

- Tobi Lütke on Organization Design and Gaming: Founder of Shopify, Lütke spoke about how he has designed Shopify’s culture to be generative and led from the bottom-up, as informed by his background in playing games such as Starcraft and Factorio. His emphasis has been on creating effective structures to manage people’s time and attention in a way that’s just-in-time. ⮨

- Pournelle’s Iron Law of Bureaucracy: Short assertion by Jerry Pournelle: people dedicated to perpetuating an organization will eventually overwhelm those who want to pursue its stated mission. ⮨ ⮨

- The Tyranny of Structurelessness: Classic article by Jo Freeman. Women’s movements in the 1970s era viewed structure as a form of tyranny, so they prided themselves on being structureless. That worked well to bring people together, but fell apart when it was time to take action. Informal political structure begins to take hold and distracts the group from being productive. This classic article advocates for experimentation and willingness to have structure and some provides principles “that are essential to democratic structuring and are also politically effective,” including delegation, rotation, and diffusion of information. ⮨ ⮨ ⮨

- Hurling Frootmig Principle: Develop work processes that are sufficiently granular that group members can grab a task and contribute as they are able. The group doesn’t need tight control for the project to continue: “…the role of the editorial lunch-break which was subsequently to play such a crucial part in the Guide’s history, since it meant that most of the actual work got done by any passing stranger who happened to wander into the empty offices on an afternoon and saw something worth doing.” ⮨

- Wind in the Willows Principle: Create group norms that allow for showing up when you can without guilt: “…and the Mole recollected that animal-etiquette forbade any sort of comment on the sudden disappearance of one’s friends at any moment, for any reason or no reason whatsoever.” Suggests making explicit a group norm of joining when you can for voluntary alliances. ⮨

- Defining interactive e-commerce: Pinduoduo pioneered a new kind of social e-commerce based on serendipity and discovery. It was built around team buying but more personal than things like Groupon. Middleman layers were removed by substituting social interactions where there would traditionally be sales. People convince each other and their friends to get deals. There is explicit modeling on “Costco+Disneyland” and inspiration from older models like tupperware parties, but the basic experience is online+mobile and genuinely social. Inspired by IRL patterns like “night market,” “sushi boat,” and “girls’ day out.” ⮨

- The Tao of IETF: Describes the “ways of IETF” and how a newbie could contribute to RFC. Founding belief embodied in an early quote about the IETF from David Clark: “We reject kings, presidents and voting. We believe in rough consensus and running code” and what became known as Postel’s Law, “be conservative in what you send and liberal in what you accept.” ⮨ ⮨

- Only Openings: A discussion by Frank Chimero of two contrasting approaches to managing wildlife in the American West and the resulting lessons for complex system design. “Some designers want to shoot the wolves, others want to manage the bears. One is trying to make an antidote, the other invests in a process to keep things open and adaptable.” ⮨ ⮨

- Steve Yegge’s Platform Rant: A famous rant, contrasting technology management practices at Amazon with corresponding practices at Google. Despite the comparison favoring Google in many small ways, Yegge argued that Amazon gets one big thing really right, making up for deficiencies in other areas—doing platform-oriented management effectively. ⮨

- Benevolent Dictator for life (BDFL): Open source software leaders who have the final say in settling disputes. Famous examples: Guido Van Rossum (Python), Vitalik Buterin. Closely related to the idea of a single wringable neck in a software development project.

- Expert Crowdsourcing with Flash Teams: The authors describe a system called Foundry designed to create block-structured workflows allowing automated management and clean handoffs to allow expert teams to do paid, coordinated work at scale.

- Guilds Reappraised: Guilds in pre-industrial Italy helped improve productivity, innovation, and quality of output. They were controlled by the most competent master-craftsman, who did a lot of the economic organizing, but also set up apprenticeship systems to pass on knowledge. Industrial changes and consolidation of government power led to the decline of the guild system.

- Underutilized Fixed Assets: Kevin Kwok argues that it is very hard to find a marketplace that wasn’t built on an underutilized fixed asset, which suggests that finding and leveraging underutilized assets is key to marketplaces.

- The Dynamic Capabilities of David Teece: “Teece originated the theory of ‘dynamic capabilities‘ to explain how companies fulfill two seemingly contradictory imperatives. They must be both stable enough to continue to deliver value in their own distinctive way and resilient and adaptive enough to shift on a dime when circumstances demand it.” Dynamic capabilities are unique to an organization and can enable it to thrive under changing conditions. Contrasted with ordinary capabilities which enable a company to reliably produce a particular outcome. Organizations need the skills for sensing, seizing, and transforming to take advantage of dynamic capabilities.

- A Systematic Logic for Platform Business Models: An ontology of business models based on three major categories: firm-centered networks, solution networks, and open networks. A forward-looking normative view based on S-D logic (service-dominant) is proposed as the best way to build platform business models.

- The Future of Platforms: There are two types of platforms—transactional and innovation, with some hybrids. Hybrids are increasing. The article analyzes platforms from a conventional business lens in terms of market performance, but doesn’t say much about their intrinsic nature or how to manage them.

- An Open Architecture for Self Organization: Bonnitta Roy’s view of an open participatory organization, based on a metaphor of a fractal network place, with two zones—core and network—and four functions—access, incubation, support, and adaptation—that create a architecture for a fluidly evolving governance that is continually regenerating it’s starting position. The key insight is that embodied thinking about change as in Stewart Brand’s How Buildings Learn can be applied to org-chart abstractions via the place metaphor.

- Single wringable neck: Who is the scapegoat when it comes to the success/failure of a software development project? Closely related to BDFL. Success has many authors but failure only one.

- Do we need a business ecosystem: A blog post from BCG Moscow defines a business ecosystem as “a solution to a business problem, as a way to organize in order to realize a specific value proposition. To this end, a business ecosystem is a governance model that competes with other ways of organizing the creation of a product or service, such as a vertically integrated organization, a hierarchical supply chain, or an open-market model.” “Unpredictable but highly malleable business environments” lend themselves to this ecosystem governance model. The key benefits of business ecosystems include access to a broad range of capabilities, the ability to scale quickly, and flexibility and resilience.

- 2020 Letter to Shareholders: Jeff Bezos’ annual public letter to Amazon’s shareholders included “be original” and “create more than you consume.” “Your goal should be to create value for everyone you interact with. Any business that doesn’t create value for those it touches, even if it appears successful on the surface, isn’t long for this world. It’s on the way out.”

- The Hierarchy of Marketplaces: Sarah Tavel makes a case that marketplaces scale by creating happiness—figuring out “how to make their buyers and sellers meaningfully happier than any substitute.” Achieving minimum viable happiness means more customers and more transactions.

* The Yak Collective started in early 2020 as an online network of indie consultants and people interested in new modes of collaboration. The principles and patterns discussed in this paper shape how we govern and make decisions within the Yak Collective. ⮨

The Yak Collective // Online Governance Study Group

Project editors / Sachin Benny and Venkatesh Rao // Project writers / Sachin Benny, Bryan King, Grigori Milov, Venkatesh Rao // Illustrations / Grace Witherell // Members / Patrick Atwater, Jenna Dixon, Scott Garlinger, Oliver King, Phil Wolff